Propaganda Is Everywhere

It may seem strange to suggest that the study of propaganda has relevance to contemporary politics. When most people think about propaganda, they think of the enormous campaigns that Hitler and Stalin waged in the 1930s. Since these campaigns happened almost 100 years ago, many believe that propaganda is no longer an issue.

But propaganda can be as blatant as a swastika or as subtle as a joke. Its persuasive techniques are regularly applied by politicians, advertisers, journalists, radio personalities, and others who are interested in influencing human behavior. Propaganda can be used to accomplish positive social ends, as in campaigns to reduce drunk driving, but it is also used to win elections and to sell malt liquor.

Defining Propaganda

As Anthony Pratkanis and Elliot Aronson point out, “every day we are bombarded with one persuasive communication after another. These appeals persuade not through the give-and-take of argument and debate, but through the manipulation of symbols and of our most basic human emotions. For better or worse, ours is an age of propaganda.” 1

These are powerful words, but what does it mean to describe something as propaganda? The critic Neil Postman once observed that “of all the words we use to talk about talk, propaganda is perhaps the most mischievous.”2

Propaganda is “the deliberate and systematic attempt to influence perception and affect behavior in ways that further the desired objectives of the propagandist.”3 Propagandists aim their messages at more than one person, and propaganda is usually distributed by an organized group.

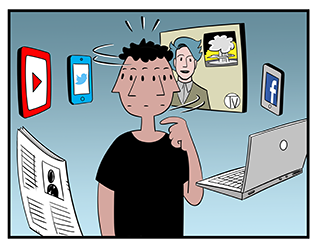

Propaganda and Social Media

Cell phones and the Internet have accelerated the flow of persuasive messages. For the first time ever, citizens around the world are participating in uncensored conversations about their collective future. This is a wonderful development, but there has been a cost.

The information revolution has led to information overload, and people are confronted with hundreds of messages each day. A growing body of research suggests that many people respond to this pressure by processing messages more quickly and, when possible, by taking mental shortcuts known as ‘cognitive biases.’

Propagandists love shortcuts — particularly those which short-circuit rational thought. They encourage this by agitating emotions, by exploiting insecurities, by capitalizing on the ambiguity of language, and by bending the rules of logic. As history shows, they can be quite successful.

During the past two decades, emerging information technologies have transformed propaganda in ways that were once unthinkable. Propagandists use computer controlled accounts called bots to control the flow of information in online forums, and they amplify the reach of these bots with the help of fake user profiles called sockpuppets. As if this were not enough, hidden persuaders are also able to use data about a user’s online behavior to figure out which messages are most likely to influence that person.

Confronted with these developments, politicians, researchers, and industry leaders have debated a range of potential solutions that government agencies and social media providers could use to combat this problem. However, we cannot rely on other people to guarantee the authenticity of messages in our information stream. Each one of us has a part to play in making things better. We can look things up, we can ask questions, and we can reflect on our own motivations for believing that a message is true.

Propaganda analysis exposes the tricks that propagandists use and suggests ways of resisting the short-cuts that they promote. This web-site discusses various propaganda techniques, provides contemporary examples of their use, and proposes strategies of mental self-defense.

Now more than ever, propaganda analysis is an antidote to the excesses of the Information Age.

References

1 Anthony Pratkanis and Eliot Aronson (1991). Age of propaganda: The everyday use and abuse of persuasion. New York: W.H. Freeman. Page 7.

2 Neil Postman (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Knopf.

3 We borrowed this definition from Garth Jowett and Victoria O’ Donnell (1986) Propaganda and Persuasion. Newbury Park: Sage. For further discussion, see: Aaron Delwiche (2007). “From The Green Berets to America’s Army: Video games as a vehicle for political propaganda.” Originally published in: J. Patrick Williams and Jonas Heide Smith (2007) The Player’s Realm: Studies on the culture of video games and gaming. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc. Pages 91-109.