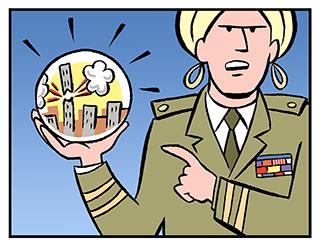

Unwarranted Extrapolation

The tendency to make huge predictions about the future on the basis of a few small facts is a common logical fallacy.

As Stuart Chase explains:

“By pushing one’s case to the limit… one forces the opposition into a weaker position. The whole future is lined up against him. Driven to the defensive, he finds it hard to disprove something which has not yet happened. Extrapolation is what scientists call such predictions, with the warning that they must be used with caution. A homely illustration is the driver who found three gas stations per mile along a stretch of the Montreal highway in Vermont, and concluded that there must be plenty of gas all the way to the North Pole. You chart two or three points, draw a curve through them, and extend it indefinitely.”1

This logical sleight of hand often provides the basis for an effective fear-appeal. Consider the following contemporary examples:

- If Congress limits the availability of automatic weapons, America will slide down a slippery slope which will ultimately result in the banning of all guns, the destruction of the Constitution, and a totalitarian police state.

- If Congress allows people to post blueprints for creating guns with 3D printers, criminal gangs will unleash a plague of violence with these DIY-weapons.

- If the United States signs the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, the giant sucking sound that we hear will be the sound of thousands of jobs and factories disappearing to Mexico.

- The emergence of cell phones and social media platforms will lead to a radical decentralization of government, greater political participation, and a rebirth of community.

When a communicator attempts to convince you that a particular action will lead to disaster or to utopia, it may be helpful to ask the following questions:

- Is there enough data to support the speaker’s predictions about the future?

- Can I think of other ways that things might turn out?

- If there are many different ways that things could turn out, why is the speaker painting such an extreme picture?

References

[1] Stuart Chase (1956) Guides to straight thinking: With 13 common fallacies. New York: Harper. Pages 41-42.