Fifty Cent Army

In December 2014, an anonymous blogger named Xiaolan hacked into the email account of the Internet Propaganda Office of Zhanggong district. The stealthy blogger leaked emails that were sent and received by the Internet Propaganda Office in 2013 and 2014. Xiaolan claimed that these emails documented communication between members of the shady 50 Cent Army.

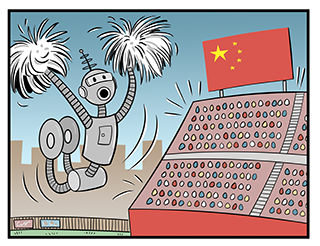

The 50 Cent Army was mobilized by the Chinese government as a vehicle for diverting critical discussion of the government in online forums. Named after an unsubstantiated claim that employees make fifty cents per post, the Chinese government hired these sockpuppets to disseminate messages praising the Chinese Communist Party on social media sites. In 2016, a study co-authored by researchers from Harvard, Stanford, and UC San Diego found that the 50 Cent Army produced approximately 448 million social media posts in China per year.1

The tactics used by the 50 Cent Army are remarkably different than those of the Internet Research Agency. These information warriors are paid to post pro-government messages, but they typically avoid arguing with dissenters.

Researchers speculate that the 50 Cent Army disrupts dissidents’ organizational efforts with the use of cheerleading, positive discussion, and complex coordination strategies that inhibit collective action. So, although individuals are not censored, their ability to organize politically is seriously constrained. By swamping social media sites with content, members of the 50 Cent Army are able to interrupt the organic flow of information. It is much harder for users to coordinate with one another when they must wade through a ton of irrelevant content to do so.

By flooding sites with positive comments, these Chinese sockpuppets effectively censor the share of user-generated information and make efforts to coordinate extremely difficult for authentic social media users. While it is clear that the 50 Cent Army is able to make it challenging for users to see content created by other users, these sockpuppets are also successful at diverting people’s anger.

Sockpuppets can successfully redirect civic discontent by posting controversial content that makes people angry. In a recent interview, an anonymous member of the 50 Cent Army explains how this works. He asks us to imagine a scenario in which the price of gas has jumped from $3.50 to $5.50 a gallon. In most nations, one would expect citizens to complain online about the sharp increase in price. To deflect blame away from the Chinese government, the propagandist might post a message saying “Rise, rise however you want, I don’t care. Best if it raises to 50 yuan (~$7.5 USD) per liter: it serves you right if you’re too poor to drive. Only those with money should be allowed to drive on the roads.”2

After posting this message, he would use other sockpuppet accounts to reply to this post, drawing attention to the message and moving it toward the top of the discussion forum. In theory, this tactic redirects popular anger toward the person who posted the controversial message rather than toward the Chinese government.

Xiaolan’s hacking skills have contributed to many significant studies by providing insight into a highly secretive organization. Contrary to popular belief, these fake accounts do not attempt to silence dissenting voices. They prefer to flood social media sites with positive content that disrupts the flow of information between authentic users.

This is effective for the government not only because it disperses millions of pro-government messages, but also because it complicates the ways in which users interact with one another. In the words of the researchers responsible for the 2017 study, “with respect to this type of speech, the Chinese people are individually free, but collectively in chains.”3

References

1 King, G., Pan, J., & Roberts, M.E. (2017) “How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Discussion, not Engaged Argument.” Working paper. P. 26.

2 Weiwei, A., (2012, October 17) “China’s Paid Trolls: Meet the 50-Cent Party.” NewStatesman.

3 Ann Hall (2015, May 20) “Fruitful connections,” Harvard University – Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.”