Anchoring

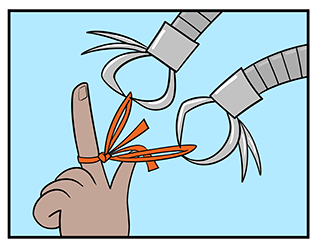

Will Rogers once famously said, “you will never get a second chance to make a first impression.” While this quip is obviously referring to the first impressions that we make when meeting other people, the same thing could be said of other first impressions. When negotiating the price of a car, the first number that is named serves as the “anchor” price. The customer then makes a counteroffer and we judge the counteroffer as being reasonable or unreasonable based on how it relates to the anchor price.1 This tendency to latch on to the first piece of information we receive is called anchoring.

In the same way that we use an anchor price when determining what a reasonable counteroffer might be, we are more likely to believe the first information that we receive about an unfamiliar topic. Propagandists take advantage of this cognitive bias by making sure that their message is one of the first things we see. Sometimes, they attempt to frame a new topic in ways that are favorable to the propagandist’s cause; at other times they contaminate our understanding of the issues by circulating logical fallacies, slanted claims, or fabricated disinformation. Because authors of disinformation do not fact-check their news, they are able to spread news stories faster than responsible journalists. Unlike authors of disinformation, journalists are held to standards that ensure their work is as accurate and unbiased as possible. While journalists are concerned with sharing the truth, people spreading disinformation are motivated by a desire to influence our beliefs and behaviors. By getting news out quickly, propagandists can ensure that their version of the story is the one that we anchor onto. Therefore, it is doubly important to use responsible media literacy skills when navigating our daily life.

A few helpful questions to consider when finding information about an event include:

- Where was this news story originally published? Is it a reputable source?

- Who is the author of this story? Is he or she a credible expert on this issue?

- If you are unfamiliar with the source or the author, you can search Google or Wikipedia to find out what others have said about their credibility.

- I don’t agree with what this source is saying. Am I disagreeing with opinions or facts?

- What trusted third-party site can I go to get a second opinion on these facts?

- Train yourself to ask “where was this published?” and “who is speaking” about all claims you encounter. Don’t worry about memorizing names and sources. Simply by training yourself to pay attention, you will gradually develop a personal framework for evaluating source credibility.