Reactance

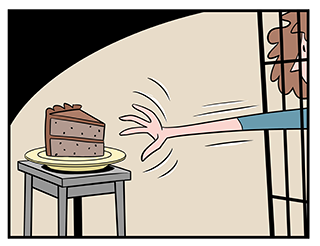

According to the psychologist Jack Brehm, most human beings do not like to have their freedoms limited. He referred to this instinct as ‘reactance.’ A great example of reactance can be seen in the following experiment. Let’s say that an authority figure (teacher, boss, parent, police officer) tells you that you aren’t allowed to touch your left arm for five minutes. Are you suddenly hyper-aware of all feeling in your left arm? Does it itch or tingle? Do you need to touch it RIGHT NOW?

In examples like the one above, a simple freedom has been taken away and we feel the need to act against it. People experience reactance in many situations. At the grocery store, advertisers try to force you to buy their green beans. In college, you have to pay tuition. At school or work, you can only use your cell phone during a break. Professor of psychology Christina Steindl and her colleagues state that the severity of our reaction to situations where our freedom is restricted will vary according to the perceived importance of the freedom that was lost. When a freedom is threatened, we feel uncomfortable, hostile, aggressive, and angry.[1] These feelings might motivate us to recover that lost freedom.

Many of these examples are light-hearted, but unethical propagandists can leverage reactance and fear appeals to convince the reader that a particular group (e.g., immigrants, conservatives, liberals, or religious minorities) wants to restrain the reader and limit his or her freedom. Reactance and fear are a toxic combination, and history shows many examples of how such rhetoric can lead to the persecution of vulnerable minorities.

Like a fear appeal, researchers have found that there are four elements that pertain to reactance. In order to feel that we have lost a freedom, we must have had that freedom in the first place. Therefore, having a freedom is the first element of reactance. The second element of reactance is when that freedom is threatened. Then, the feelings of discomfort and aggression that result after a freedom is threatened bring us to the third step of reactance. Finally, the last element of reactance is the act of restoring the freedom that was lost. By making an audience believe that a freedom is being threatened, propagandists can motivate people into action. Propagandists might over-exaggerate situations to make them appear more threatening than they actually are to appeal to our emotions rather than giving an argument based on factual evidence.

Some questions to ask yourself might include:

- If a speaker argues that your freedom is under threat, ask yourself if this is objectively true. Is a freedom genuinely under siege?

- If a speaker argues that your freedom is being impinged, consider whether or not this is a meaningful deprivation that genuinely matters to you. If the propagandist had not raised the issue, would you ever have considered engaging in this particular behavior?

- Assuming that a meaningful freedom is genuinely at risk, how likely is it that the speaker’s recommended course of action will restore that freedom?

- Is this message aimed at a certain group of people (e.g. the middle class, immigrants, dentists)?

- If a speaker claims that a minority group threatens your freedom, do some quick online research to find out what else the source has said about this particular minority group. This can help you decide if the speaker has a tendency to blame this minority group for all sorts of social ills.

References

[1] Christina Steindl, Eva Jonas, Sandra Sittenthaler, Eva Traut-Mattausch and Jeff Greenberg (2015) “Understanding psychological reactance,” Zeitschrift Fur Psychologie. 223(4): 205-214. DOI: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000222.