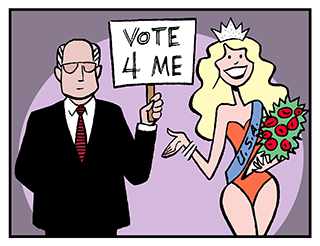

Testimonial

Steph Curry is on the cereal box, promoting Wheaties as part of a balanced breakfast.

Sofia Vergara is endorsing a new line of cosmetics, and the Kardashian/Jenner sisters claim that the weight loss supplement QuickTrim changed their lives.

As the IPA explains, the Testimonial Device “consists in having some respected or hated person say that a given idea or program or product or person is good or bad… [S]ome of these Testimonials may merely give greater emphasis to a legitimate and accurate idea, a fair use of the device; others, however, may represent the sugar-coating of a distortion, a falsehood, a misunderstood notion, [or] an accidental suggestion.”1

But everyone knows this, right? When we see this technique online, we smile to ourselves. We know that we are smart enough to see through such obvious manipulation. Then, in the very next breath, we turn to our friend and say “Did you hear what Morgan Freeman said about the health risks of eating too much tuna?”

There is nothing wrong with citing a qualified source; the testimonial technique can be used to construct a balanced argument. However, this source should be credible in the context of the speaker’s claim.

The most common misuse of the testimonial involves citing individuals who are not qualified to make judgements about a particular issue. In 2016, Lady Gaga supported Hillary Clinton, and Clint Eastwood threw his weight behind Donald Trump. Both are popular performers, but there is no reason to think that Lady Gaga and Clint Eastwood necessarily know what is best for the United States.

Morgan Freeman is not the world’s most authoritative expert on methylmercury toxicity, but he certainly has well-formed opinions about the motion picture industry and has had experience operating a successful nightclub.

A medical doctor is not able to offer much useful advice about projecting your voice when performing King Lear at “Shakespeare in the Park,” but she certainly has credibility when warning you to limit tuna consumption to no more than three cans per week.

Misleading testimonials are usually obvious. Most of us have probably seen through this rhetorical trick at some time or another. But here’s the thing: We are far more likely to see through the deception if the celebrity is someone we do not respect. When the testimonial is provided by an admired celebrity, we are much less likely to be critical.

A variation of the testimonial device occurs when the speaker makes vague references to experts without actually naming a specific source. For example:

“All of the greatest legal minds agree that this legislation is the only solution to our crowded courts.”

“A lot of doctors are saying that my opponent has no understanding of how the health care system actually works.”

In both of these examples, the speaker makes a testimonial claim without actually sharing specific details that the audience could use to evaluate the claim’s credibility. Who are these greatest legal minds? Who are these doctors?

According to the Institute for Propaganda Analysis, we should ask ourselves the following questions when we encounter this device.

- Who or what is quoted in the testimonial?

- Why should we regard this person (or organization or publication) as having expert knowledge or trustworthy information on the subject in question?

- What does the idea amount to on its own merits, without the benefit of the Testimonial?

You may have noticed the presence of the testimonial technique in the previous paragraph, which began by citing the Institute for Propaganda Analysis. In this case, the technique is justified. Or is it?

References

[1] Alfred McClung Lee and Elizabeth Bryant Lee (1939) The fine art of propaganda: A study of Father Coughlin’s speeches. Harcourt, Brace, New York. Pages 74 to 75.